In the third chapter of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, the novel’s protagonist, Ishmael, enters the Spouter Inn in search of passage onto a whaling ship. He soon encounters an age-darkened oil painting in the entranceway and becomes perplexed. The canvas is so covered in scratches and smoky residue that it’s all but impossible to make sense of. Throwing open a window to gain more light, Ishmael attempts to describe what he sees:

what most puzzled and confounded you was a long, limber, portentous, black mass of something hovering in the center of the picture over three blue, dim, perpendicular lines floating in a nameless yeast. A boggy, soggy, squitchy picture truly, enough to drive a nervous man distracted.1

Ishmael renders the painting virtually abstract, or non-objective, as his act of interpretation comes to an impasse. But his comprehension of the image is not merely blocked by the marred, smoky surface. The materiality, or “thingness” of the work simultaneously frustrates, and fascinates him by denying him access to its meaning. I think of this truculent, besmoked painting often, especially when contemplating the growing allure of socially engaged art among younger artists, including those students who, by dint of previous training, lean toward craft-based object making.

Anyone who teaches visual art is familiar with the following problem. Two seemingly opposite pedagogical poles appear to be collapsing. On one side is the singularity of artistic vision expressed as a commitment to a particular material or medium. On the other is an ever-increasing pressure on students to work collaboratively through social and participatory formats, often in a public context outside the white cube. One of the most common catchall terms for the latter tendency is social practice art. Currently, there are about half a dozen college-level programs promoting its study. However, if you include the many instructors who regularly engage their students in political, interventionist, or participatory art projects, the tilt toward socially engaged art begins to look more like a full-blown pedagogical shift, at least in the United States.

The studio art classroom, as opposed to the lecture hall or seminar space, is where these contradictions are most apparent, and often most disarming. Any given cohort of entry-level students (graduate or undergraduate) includes both object makers and social practitioners. Similarly, the faculty at non-specialized art schools, and universities tend to express a range of aesthetic interests with varying degrees of engagement in art’s material production. But most significantly, the studio classroom is where art’s institutional socialization begins, and where the student encounters a very contemporary problem—let’s call it the ontological crisis of artistic subjecthood—the infinite regress of self-definitions and anti-definitions that have plagued every nascent artist since Marcel Duchamp and Moholy Nagy’s rejection of the “magic of the hand.”2 If one can purchase plumbing equipment and successfully display it in a museum, or have an abstract artwork made to order over the telephone, then what exactly defines the artist today, at least in a professional sense? The assembly line studio practices of artists like Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons serve to exacerbate this crisis. Uncertain about the fundaments of their profession, instructors (like me) perform a kind of ontological triage on identity-punctured art novices. (I will confess that this surgery is often also an act of self-healing.)

Stephen Wright may not be the first cultural theorist to link contemporary art’s object-anxiety with the definitional crisis of the contemporary artist herself, but Wright is distinguished by his view of this ontological precariousness as a potentially liberating moment, rather than as a problem to solve. He writes, “Envisaging an art without artwork, without authorship, and without spectatorship has an immediate consequence: art ceases to be visible as such.”3 Without a visible “work,” sans artistic reception, there would appear to be no way in which Wright’s militantly discreet cultural labor could be framed as art, not even by the “art police.” Adopting philosopher Jacques Rancière’s definition of the aesthetics of politics, Wright rejects the manner in which critics, curators, and art historians delineate the category of art and amplify one cultural discourse over the noise of others.4 By embracing, rather than avoiding invisibility, everyday occurrences, and noise, Wright elaborates a way for artists to leap out of prescribed aesthetic frames, past the policing of artistic borders, and move directly into a cultural “usership” within non-art social relations, including political activism.

Initially, this program would appear to fulfill a certain early-twentieth-century avant-garde injunction that art must dissolve into life, while aligning itself with certain 1960s conceptual artists who sought to become autodidacts in collaboration with “citizen’s initiatives, amateur scientists’ projects, and so on.”5 Except that both of those efforts landed art back in private and museum collections. But let’s say that Wright’s un-framed usership is conceivably already taking place; just think of the explosion of informal, noisy cultural activity associated with Occupy Wall Street.

In an unexpected move, OWS has not embraced invisibility or rejected an audience. Rather the movement instead has claimed its own cultural terrain, and has done so in full public view. OWS confronts the police, both literally, as well as figuratively, interweaving both short-term tactics, and longer-range strategies for returning privatized space to common use. It’s as though something long held back was streaming forth, suddenly animated, but bringing along with it a shadowy archive of other histories, and other attempts at self-realization, like a surge of long-silent dark matter spilling irrepressibly into the light. This emergent swarm-archive insists that the hazy, smoky residue of time become noisily present for all to see.6 In a rapidly gentrifying city like New York the materialization of the past is always a challenge. Meanwhile, Zuccotti Park and other OWS encampments revealed a mix of high-tech digital media and handmade signs, a mix of the archaic and the new as if beneath the internet there is cardboard.

All this complicates the classroom context. After all, instructors can hardly follow Wright’s prescription simply by refusing to engage with art’s institutional frame, at least not until before that glorious moment when all delimiting social divisions are swept away in the ecstasy of revolution.7 Prior to that day of liberation, any failure to reproduce one’s own academic field simply amounts to professional suicide. On the other hand, dissolving art into a corrupt world appears equally dishonest, and merely adds fuel to a neoliberal agenda that seeks to eliminate all economically “useless” areas of study as philosophy, poetry, classical languages, and all other non-commercial forms of “culture.”8

I teach at a school where a significant number of undergraduate and graduate students make paintings, sometimes in a traditional way, which is to say, in a realistically representational, mode, and other times they produce a variation of post-war abstraction. I do not claim that this necessarily excludes the realm of “the social” as a concrete presence, especially as it manifests itself nowadays in the omnipresence of portable electronic devices linked together through the internet. Digital images turn up as source material for student drawings and paintings; while working from photographic sources is hardly new, it seems that portraits of friends, family, pets, and self are more captivating when rendered in low resolution with acidy smart phone colors. Fast-paced paging through crowd-sourced databases such as Flickr or Google has also become second nature when researching new project ideas. But more to the point, a certain compulsory “connectivity” infests student art assignments, even those rooted in traditional media. One young student of mine made oil paintings of strangers she had image-grabbed from live video chat room encounters. At her final critique, she opened a laptop and an assortment of random online voyeurs dropped in to watch us. First, a duo of giggly women appeared, followed by a young man who stared blankly at us from the other side of a webcam, apparently masturbating just out of frame. Naturally, issues of privacy emerged (our privacy, as well as that of the online strangers), and this provided an opening for us to explore broader issues of what constitutes artistic subject matter nowadays. Nevertheless, until the laptop was at last snapped shut, the intrusion of “the social” into the classroom oscillated between diversion and disruption as the specificity of the student’s paintings faded further into the background of our discussion.

Granted, this example is somewhat superficial and represents only the outward collision between older, skill-based art traditions and portable electronics / social networks. Far more difficult to nail down is the place of “archaic” media such as drawing, painting, and sculpture in the sphere of social practice and performance art. No doubt some of you will think of street art, protest props, or papier-mâché puppets. Or perhaps what comes to mind are those climate-controlled layers of lard and honey and felt that once accompanied lectures by iconoclast Joseph Beuys, and that nowadays sit in some swanky kunsthalle, art center, or museum. Once again, to go beyond shallow assumptions of social media’s invasion of traditional art practices, let me put the question differently: Where does abstraction and the non-representational intersect with the social? Or, put the other way around: What is the limit of the social within the social itself? I wish to propose that one way to approach this question is through Jane Bennett’s concept of the agency of “thinghood,” the “material agency of natural bodies and technological artifacts.”9

Bennett, a political scientist by training, wants to articulate a non-human materiality in much the same way that Michel Foucault explored culture as an objectified force of human affect and desire, most famously including institutional discipline. Bennett, however, introduces us to a world of vibrant matter, in which concrete forces sometimes appear as obstacles to overcome, and sometimes as obstacles that overcome us (consider Hurricane Katrina in 2005, or the massive Japanese tsunami of several months ago). Ultimately, these extra-societal agencies must be understood as forces to be reckoned with, as well as engaged with,10 though always in a critical manner.11

The recognition of a resistant thingness at work within the social, including those human-originated technologies that have gone on to operate virtually independent of us, may in fact mark a point of conceptual convergence for those contrary artistic poles discussed above: the immaterial, social practitioner and the studio-based artist. Note how artist, activist, and teacher Doug Ashford, who worked with the socially engaged artists’ collective Group Material for over fifteen years, grapples with the role of the abstract object in a series of paintings he has worked on over the past few years:

I’m wondering what it means these days to employ abstract images as a participant in social organizing efforts. For many years I was a collaborator in Group Material, an artistic process determined by the idea that social liberation could be created through the displacement of art into the world, and the world into the spaces of art.12

Ashford seems to suggest that his current interest in abstract art and object making was foreshadowed by Group Material’s collaborative installation practice. In 1990, he and other members of the collective organized the “Democracy” exhibition for the Dia Art Foundation’s short-lived exhibition space on Mercer Street in Manhattan. They transformed Dia’s gallery into a classroom, complete with rows of desks and chalkboards. Around the “classroom” hung a selection of artwork arranged “salon-style” overlapping against bright red walls, an anti-white cube gesture similar to a Group Material design “signature.” With “Democracy,” as with many of their installation projects, the collective sought to generate a different kind of space within the art gallery, a social arena in which learning could take place directly or indirectly through an art whose form and/or content focused on questions of inclusivity and participation:

Today I’m interested in how our exhibition designs assigned democracy’s unpredictability and inclusivity to an imaginable shape, a shape you could feel, a shape that is always irregular and fluctuating: an abstraction.13

Ashford takes his hunch a bit further, in the form of a challenge: “Is abstract painting a clue to the irregular shape I experienced at Group Material shows and our modeling of democracy?” Can something so abstract even be visualized? Or is the question really about the intersection of a certain aesthetic vocabulary with everyday social routines? After all, Group Material’s project is but one attempt by artists to make something ineffably abstract into a concrete force or agency, or to attempt the opposite by dematerializing the well-worn world of the social into an aesthetically informed spectacle through the strange agency of abstraction.

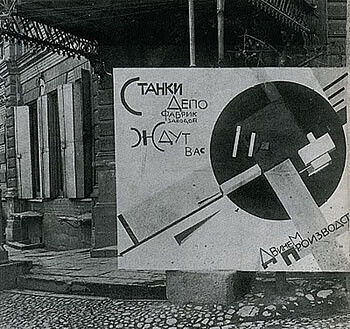

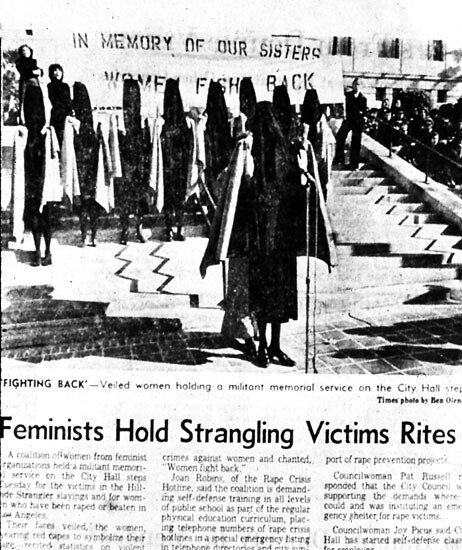

Grainy images of large, suprematist shapes in the streets of 1920s Belarus flash up in my mind as I write this last sentence. Aimed at inspiring new ways of thinking and new forms of organizing during the early years of the revolution, these startling plastic forms were generated by Soviet Commissar of Art Kasimir Malevich and his colleagues at the Vitebsk School of Art. Suprematist pedagogy also took place inside the classroom. Students not only constructed three-dimensional geometric forms in a radical break with realist traditions, they also understood abstraction to be central to the realization of a new “creative collectivity.”14 This mental recollection is replaced by another black-and-white photograph, this time on the cover of the Los Angeles Times. It depicts Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz’s discerning 1977 media event In Mourning and in Rage, which was staged before news cameras on the steps of Los Angeles City Hall to call attention to the victims of the brutal Hillside Strangler. The performance begins with a troupe of preternaturally tall, veiled figures slowly emerging from a funeral hearse to silently protest a culture they believe promotes female victimhood.15 The concise geometry of the forms and staging is a quintessential Western artistic trope morphed into public spectacle in pursuit of social justice. But there is a reciprocal way to examine the agency of thingness and social practice, one that is less about abstract forms intervening in social content, and more about the social itself as a kind of abstraction, or perhaps more accurately, as a merging of biological agency with mechanical and mnemonic forces.

Operating the “people’s microphone,” or “human microphone,” is simple enough. Made famous by OWS as a response to a New York City ban on amplified sound at Zuccotti Park, a group of listeners broadcasts a speaker’s words by loudly repeated them in unison. For larger gatherings, a second wave of repetition is sometimes necessary. On one level, this cultural innovation appears to be a “flesh and blood” substitute for an electronic technology that large public meetings have come to depend upon. On another level, the people’s mic introduces mechanization directly into human-to-human interaction by alternating segments of speech with interruptions to generate gain, a series of discontinuous procedures that send physical ripples through a congregation transformed, one could say, into a temporary, self-regulating cybernetic community, an undulating cyberorganism. Likewise, the entire OWS panoply of hand-drawn or pirated imagery —made with thin-point or chisel-tipped markers, bits of torn masking tape, clipped newspaper, collaged laser prints, spray paint stencils, as well as charcoal and acrylic, and limitless pieces of recycled beige cardboard— exhibited the unmistakable qualities of an archive even before the encampment was power-scrubbed into history. Here I am approaching the idea of the archive not as a precise collection of thematic documents that uphold this or that school or historical interpretation, but instead envision it as a site of conceptual “objects,” as well as an unbounded material accumulation capable of becoming a force of spirited intervention in the present. In this sense, Zuccotti Park, along with all other OWS encampments, embodies an archive avant la lettre, that is to say, a collection of materials, biopolitical practices, and everyday concrete documents waiting to be recognized as an interpretable text. Sadly, in New York City, the moment of this “reading” began at 1 a.m. on November 15 when the NYPD began to clear the park.

Embracing Bennett’s material vibrancy within social practice means recognizing not only the role of extra-human technologies and abstract concepts like democracy, but also the corporeal presence of “nature,” not in some sugary, universal form, but as a negation that radically confronts human culture with alterity. This line of thinking might, for instance, nudge a project focused on the interaction of human and natural ecologies within a downtown waterfront or inner-city park—to cite a couple of examples I am familiar with—into a reflection about what the river might demand from society, as opposed to what it offers city residents.16

Likewise, if we think of putting “art” to work explaining or engaging participants in an abstract notion like democracy, as Group Material sought to do, we could, with more effort, turn this procedure around and consider how an abstraction like democracy might manifest itself in physical, even aesthetic forms. At the same time that art’s previously hidden sociality materialized within OWS, or the internet, or via the steady stream of collective practices that have blossomed over the past fifteen years, there is a danger that a range of techniques, non-discursive ways of thinking, and material forces will be rendered obsolete, regressive, or invisible. Such an approach might also help terminate endless debates about artistic deskilling whose concrete art-world manifestations have less to do with theoretical niceties like immaterial labor than they do with the unspoken hierarchy between a class of idea-artists and a lower class whose skills are called upon to fabricate projects.

Returning to the darkness of the Spouter Inn, Ishmael eventually believes he can recognize what the obscure mass at the center of the half-lit painting represents. In a reading foreshadowing the impending drama, he offers

a final theory of my own, partly based upon the aggregated opinions of many aged persons with whom I conversed upon the subject. The picture represents a Cape-Horner in a great hurricane; the half-foundered ship weltering there with its three dismantled masts alone visible; and an exasperated whale, purposing to spring clean over the craft, is in the enormous act of impaling himself upon the three mast-heads.

Perhaps, rather than thinking of social practice art as a strategy for unlikely survival against the forces of neoliberal enterprise culture and its strip-mining of creativity, we could inscribe this still-emerging narrative with a stubborn sense of materiality and a vibrant itness, that if nothing else would challenge unspoken hierarchies, and divisions of labor, because a critical, social practice should above all acknowledge the limits of the social within the social itself.

Herman Melville, Mobu-Dick: or, the Whale (Waking Lion Press, 2009), 7.

See the interview with Marcel Duchamp following his “retirement” from making art.

Stephen Wright, “Users and Usership of Art: Challenging Expert Culture” (2007), transform, →.

Rancière’s definition of the police is cited by Wright, ibid.

Wright’s text does not focus as much on the artist’s troubled identity as on artistic reception; I have therefore taken some liberties in applying his thinking to the question of practice itself.

For more about OWS and the concept of the archive, see my forthcoming text “Occupology, Swarmology, Whateverology: the city of (dis)order versus the people’s archive,” in the online version of Art Journal. And about the concept of art’s missing mass, see my book Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011).

I am referring here to Karl Marx’s oft-quoted remark from The German Ideology that “in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.”

For an excellent reference to this process of corporatized education, see Edufactory Journal, →.

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Duke UP Books, 2009), xiii & 1.

Ibid, 4.

Jane Bennett is not the first thinker to take materiality and its affect on art, science, or politics seriously. Certainly Theodor Adorno’s concept of negative dialectics grapples with the category of nonidentity, applying it not only to the realm of ontology, but also to aesthetics, and in ways that exceed in their critical force such currently fashionable writers as Jacques Rancière. But Bennett explicitly distances herself from this approach, arguing that Adorno still holds out hope of reconciling the unspeakable otherness of things with human knowledge (Ibid, 14), and that Rancière admits only those who can engage in human discourse into the realm of political participation, thus leaving aside other beings, forces, animals, and things (Ibid, 106). By contrast, Bennett’s vibrant matter acknowledges the full-on agency of the non-human in itself, without need for human definition, acceptance, instrumentality, or intervention. Still, I suspect that despite her resistance to Marxism, Bennett’s ideas are strangely closer to those of Walter Benjamin, perhaps more so that she might acknowledge. I am thinking here of Benjamin’s positive appraisal of surrealist photography in which everyday things dulled by familiarity reassert themselves through uncanny estrangement. But also his interest in the politics of dreaming and fantasy, let’s call this the vibrancy of the historical unconscious, or of the archive from below.

All quotes are from Doug Ashford and Angelo Bellfatto, “Sometimes We Say Hopes, or When We Want to Say Hopes, or Wishes, or Aspirations,” in Interiors (Bard CCS and Sternberg Press, forthcoming), originally presented as a conversation at The New Museum, April 29-30, 2011.

Ibid.

Aleksandra S. Shatskikh, Vitebsk: the Life of Art (Yale UP, 2007), 137.

See →.

Nicholas Mirzoeff writes about an attempt to “occupy” the recent UN Climate Change Convention in Durbin, South Africa by indigenous people who call for the “decolonization of the atmosphere,” a tacit recognition of the planet’s rights, in “Occupy Climate Change,” Occupy! Gazette 3 (December 15, 2011): 32, 34.